Early Cotton and Textile Production in Nicaragua

Cotton was already being used as a textile in Central America when the Spanish arrived in the 15th century. In 1548, some 20 years after their arrival in Nicaragua, the Spanish imposed a tax on the indigenous peoples which they paid in the form of textiles, among other things. Historians tell of the beauty of the indigenous fabrics, pieces of which are still in existence.

Cotton was cultivated and woven in Nicaragua until the mid-twentieth century. The kind of plant that grows in Central America is a 3-4 meter bush that yields small fibers that make fine fabric. Called Panilla (broiled), it is more laborious to spin than other species of cotton. It’s generally white in color but sometimes appears in brown, yellow and light green as well.

Evidence of Early Dying Practices

Archeologists have found evidence of early cotton textiles throughout Latin America. Some, such as the strips found in South American tombs, are undyed. Others were dyed with all manner of things, from plants to shells and even snails, which early artisans squeezed for their color before returning them to the sea.

It was not until the 19th century that chemicals were introduced into the cotton cultivation and dyeing processes. The 500-year-old fabrics dyed naturally, however, have preserved their color much better than those dyed with artificial means.

Many samples of these early textiles have been preserved in Nicaragua. Two indigo-dyed pieces of over 100 years old are on display in a museum in Nindiri, and another of the same age in Masaya that is the color of coffee. A few more ceremonial pieces have been preserved in the village of El Chile, home of the Telares weavers.

El Chile, a proud history of weaving

El Chile has been famous for its weavers for centuries. Historically, women who produced woven fabrics were called “Manteras.” The tradition was so strong in El Chile that it was one of the last communities to stop wearing homespun fabrics after the influx of pre-manufactured garments from England began in the early 20th century.

Nicaraguan textiles are characterized by their simplicity, in contrast to their northern neighbors in Guatemala who traditionally use bright colors and floral designs. According to former Minister of Culture Father Ernesto Cardenal, however, Nicaraguan weavers have also employed brighter colors in the past.

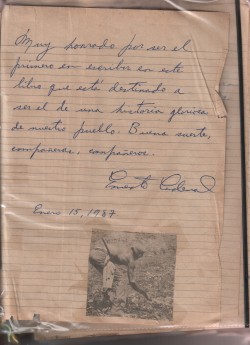

Ernesto Cardenal’s entry in the Telares guestbook in January, 1987

Prohibition by the Somoza Regime

The women of El Chile continued weaving until 1950, when the Somoza regime banned the cultivation, spinning and weaving of cotton and other fabrics. The reason for this prohibition is unknown, though some theorize that it was done to reduce competition with the Somoza-owned cotton factories or to free up labor for the fields of nearby landowners. Others believe the move was made to weaken the culture and demoralize the people. Whatever the reason, the effect was a total cessation of the craft for more than three decades.

When the Somoza regime fell, the new Sandinista government wanted to bring back indigenous crafts like weaving. An Argentine woman working for OXFAM-Belgium traveled to Nicaragua in 1984 to do just that. Her name was Marta Ruiz.

Marta traveled to the village of El Chile for the first time in the early 80s, looking for people who remembered how to weave. She was joined in her revival effort by Father Cardenal, who had just been appointed Minister of Culture by the new government.

Four elderly women in El Chile still knew the craft, but were reluctant to use it out of fear. Finally, another woman came forward saying that she had observed her grandmother doing it and thought she knew how. With the help of that woman, Plácida Hernández, Marta and Father Cardenal were able to train a group of young women, first with the traditional belt looms and later with foot pedal looms imported from Europe. The government paid them during their training so that they would not be forced back into the fields to feed their families.

Continuing the Tradition

The work led by Marta from 1985 – 1995 allowed some 100 women in El Chile to learn to spin and weave cotton. For many years, Marta lived in the community until 2010 when she began spending part of each year in Europe. To this day she is known as “Marta of El Chile.”

From that original group of young teenage girls, Telares Nicaragua was born, and from Telares a few other groups of weavers. The activity that began as a cultural revival has become a productive and self-sustaining business.

Francisca, Virginia, Julia and Azucenca, Telares members that were trained by Marta in 1985, describe their work: “Currently we are a group of organized and technically-trained women with experence designing and assembling all kinds of different products. We created and run our organization ourselves.”

Marta and The Group